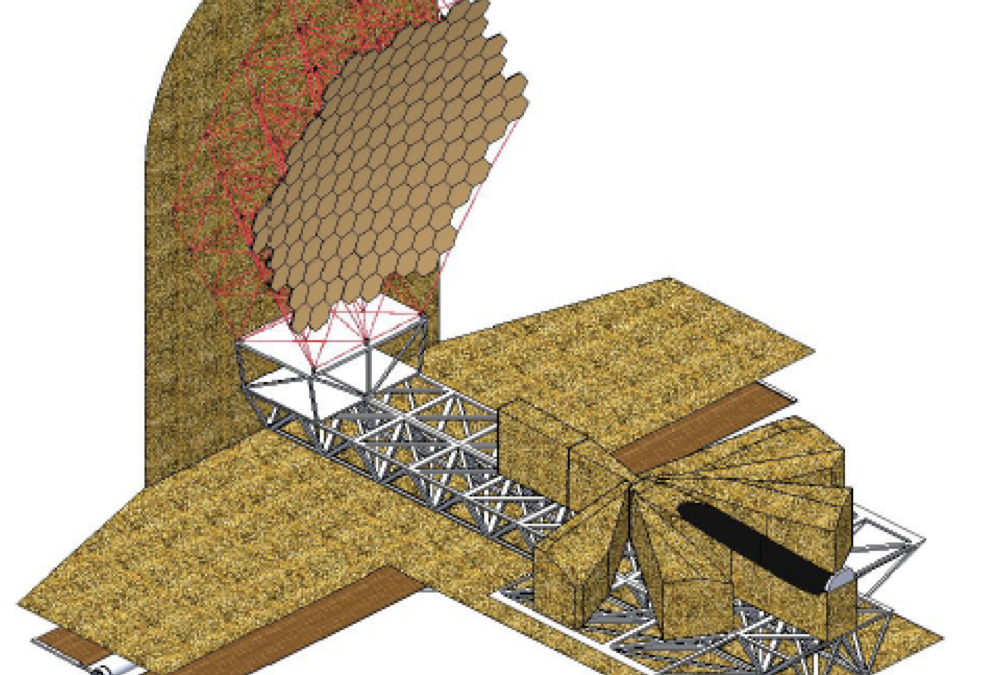

[Concept for an in-space assembled telescope, from the NASA 2019 ISAT study. Credit: NASA]

Two telescopes, operating in space, are transforming our understanding of the universe. The Hubble Space Telescope is known around the world for its breathtaking images of galaxies, new-forming stars, and other astronomical phenomena. Much more recent, more powerful, but perhaps less well-known, the James Webb Space Telescope is complementing Hubble, but also looking deeper into the past (farther away from us, the same thing) and looking at different parts of the spectrum.

Two points of comparison are important. Point one: JWST’s 18 mirror segments combine to an equivalent aperture of over six meters, giving almost ten times the light collecting power of HST’s 2.3 meter mirror. Point two: HST was designed to be serviced–to have its instruments upgraded over time–which has kept it scientifically useful for over twenty years. It also enabled replacing some failing components, like gyroscopes and batteries. JWST’s instruments cannot be replaced. It will, at some point, become obsolete, even if no repairs are required.

NASA is now thinking ahead to the next great astrophysics observatory. The working name for this system, which aims to be launched in the 2040s, is the Habitable Worlds Observatory. This hints at one of its highest scientific priorities: taking measurements on exoplanets to see which ones might have atmospheres similar to Earth’s, and therefore capable of sustaining life. Here is a recent article on HWO:

https://www.space.com/space-exploration/search-for-life/nasa-wants-a-super-hubble-space-telescope-to-search-for-life-on-alien-worlds

When NASA Administrator Bill Nelson first announced HWO, his statement included that it “will be serviceable.” I was briefly part of a Technology Advisory Group for HWO that was trying to put some meat on that statement. What does serviceable mean for HWO? Instrument replacement, or merely life extension? And how should that be accomplished? How will the design of the telescope be affected by serviceability?

After a few months of government-industry collaboration, the initial concept development became a government-only activity. The community is waiting to see what comes of this. But there is the possibility for an opportunity to be lost: ensuring that not only will the telescope be serviceable, but that it be ASSEMBLED ON ORBIT BY ROBOTS from parts brought up on multiple launches. This is a critical step which promises reduced risk, reduced cost, and more benefits to the space industry.

Why do I say this? Five years ago, NASA had assembled a group to consider the on-orbit assembly of a large telescope. Called the In-Space Assembled Telescope (ISAT) study, it found that for a primary mirror of 8 meters or greater, on-orbit assembly would actually be cheaper than trying to launch the telescope all at once. Coincidentally that’s also about the size where it’s IMPOSSIBLE to launch on a single ride, because launch vehicle fairings (even Starship and New Glenn) aren’t that big.

But robotic on-orbit assembly also reduces risk to the program, in at least two ways: if a launch vehicle fails, you only lose some parts that were being delivered, not the whole instrument. And if any parts are found defective once they arrive on orbit, you simply launch replacements.

The ISAT study can be read here:

https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/exep/technology/in-space-assembly/iSAT_study/

NASA should ensure that the HWO studies give robust consideration to the robotic on-orbit assembly alternative.

Recent Comments